Seven years since Paris, as an industry are we doing enough on climate change?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recently published the 6th edition of its reports on climate change mitigation. An impressive tome put together by over 600 scientists from 65 countries – which is apparent both from its diligence and accessibility. The report is upbeat in as far as confirming we have the tools available to reach a net zero position, the existential question is can we do it quickly enough to avoid the worse extremes of climate change. As an industry, we have a role to play in delivering greener generation, which also featured heavily in the 2018 report, as well as in two other areas of increasing prominence: demand reduction and carbon removal. Solutions are available with no, or relatively little, subsidy in many of these areas.

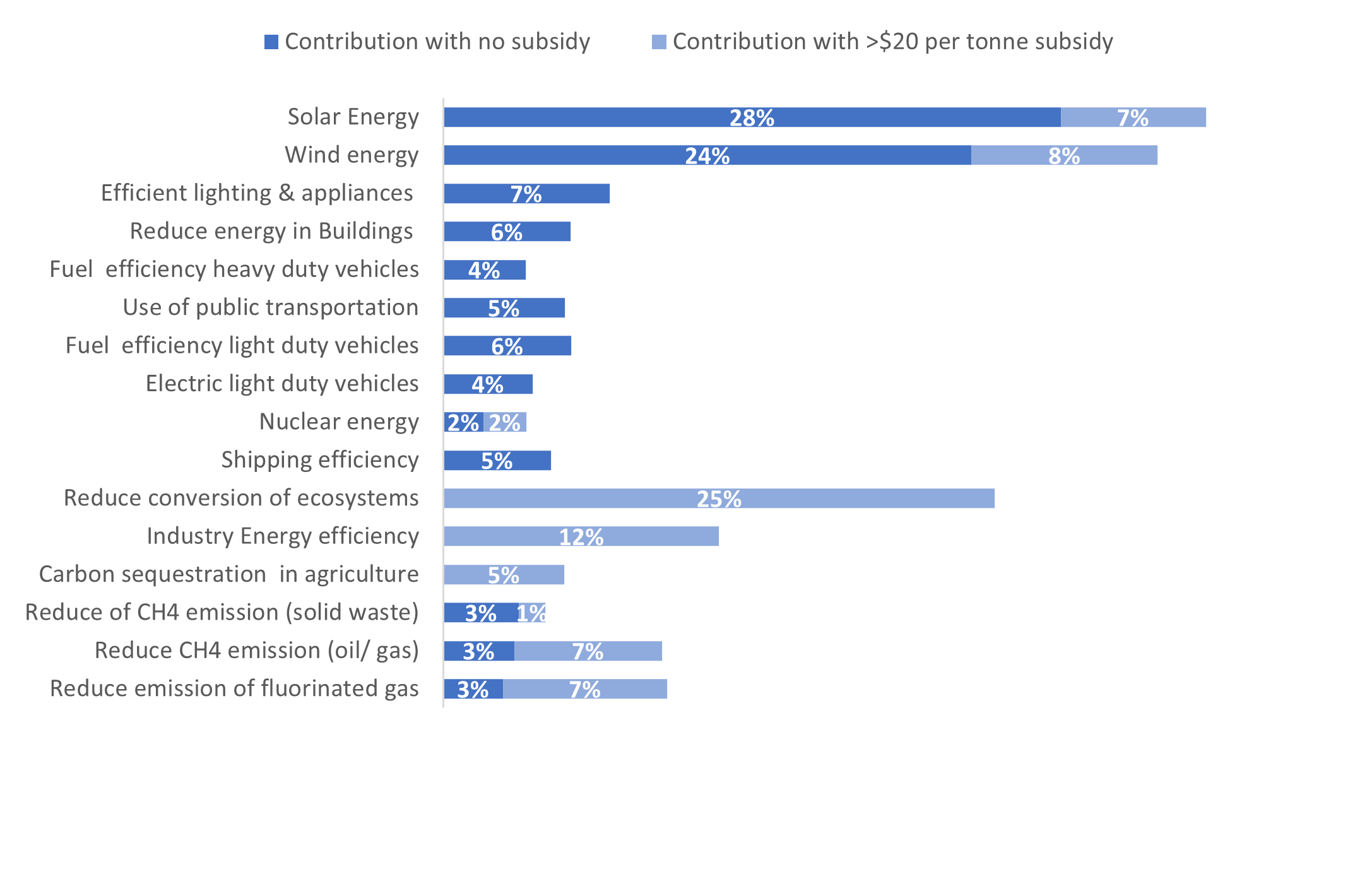

By 2030 we need to reduce annual emissions globally by c. 20 gigatonnes of CO2 (equivalents) per year to be on the 1.5°C path set out by the Paris Agreement and by c.12 GtCO2-eq for the 2°C path. The IPCC report sets out a shopping list of options. They estimate that c.10 GtCO2-eq could be done with commercially viable technologies and a further c.9 GtCO2-eq with technology which requires a subsidy of less than $20 per tonne of CO2 (by comparison petrol duty in the UK is equivalent to $300 per tonne). While this is global analysis, and priorities vary across regions, this is a useful framework from which to assess our performance in the UK and it provides the detailed analysis lacking from the government’s “Path to Net Zero”. The chart below sets out the technologies, with no subsidy or subsidies of less than $20 per tonne, which can make the greatest potential contributions to reaching net zero.

Figure 1: Analysis of the data taken from SPM.7 of the IPCC report. Shown as % of total contribution estimated for each category of subsidy. Further information here.

Greener Generation:

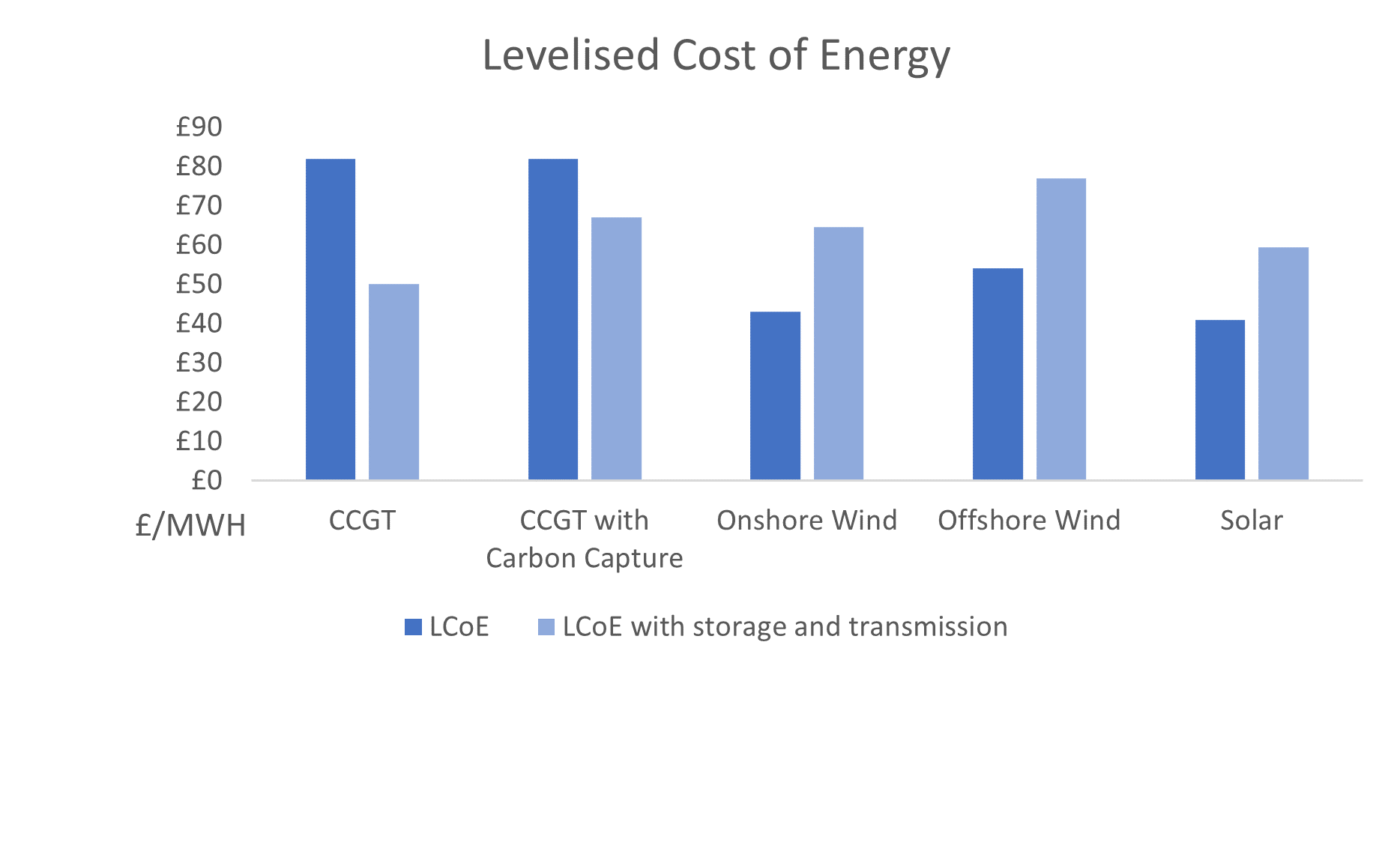

Wind and solar are looking increasingly competitive based on levelised costs of energy including grid and storage requirements, as outlined in the graph below. With gas prices rising significantly over the past 18 months due to increasing demand and supply constraints, most recently as a result of the war in Ukraine, renewables have become even more competitive.

Figure 2: BEIS 2020 projections for plants commissioning in 2025 (Table 7.2 p.45) Full report here

There is a coalesced view that Nuclear is a key part of the energy transition, supplying much of the UK’s base load of low carbon power. Historically private sector investors have been wary of the sector. To change this the government are looking to use the RAB model which has been successful in the regulated utilities. Hope is being pinned on Small Modular Reactors – which at up to 300MW a pop are not that small – to bring the cost and delivery time down but there is still some way to go with this technology.

Demand Reduction:

As well as ensuring energy consumed comes from low carbon resources, the IPCC report highlights the important role demand reduction has to play. Behavioural change is an important factor in demand reduction, but infrastructure investors also have a role to play, for example by investing in energy efficiency technologies.

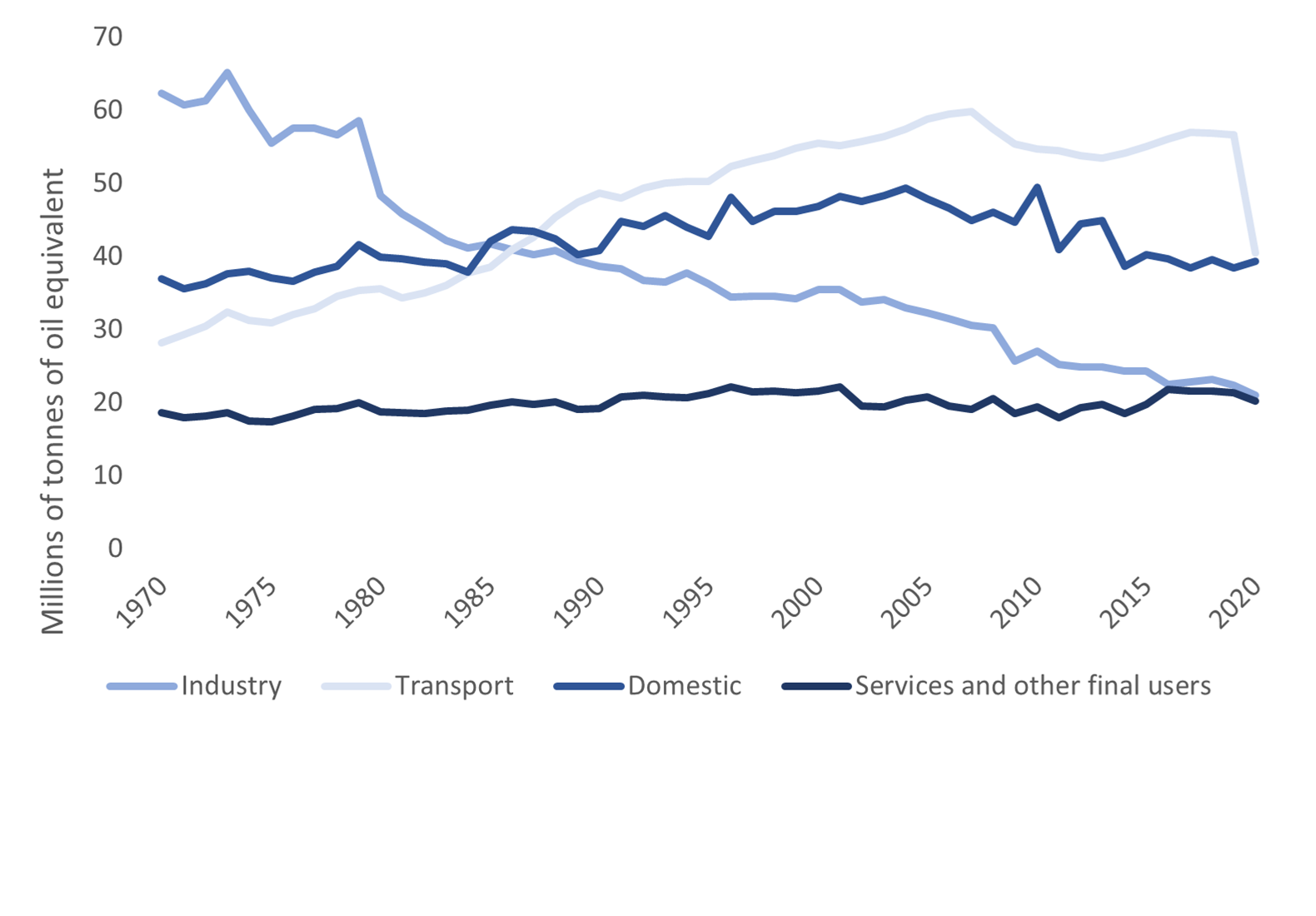

The graph below shows impressive reductions in the emissions from industry in the UK over the last 50 years, however this may not tell the whole story if some emissions are simply offshored. The services and transport sectors have seen a decline in the past couple of years, the latter showing a significant decline attributable to the pandemic. Although demand reduction in transport may rebound, it feels like electrification of the sector has reached a tipping point. Addressing the decarbonisation of domestic consumption (and in particular heating) remains a major challenge.

Figure 3 : BEIS Energy Consumption in the UK (ECUK) 1970 to 2020, full report here

Carbon capture:

As we fall further behind the path set in 2018, carbon capture becomes an increasingly important part of the puzzle. It is also the solution for areas with no discernible route to decarbonise. The ecological side (such as ecosystem restoration or sequestration of carbon in agricultural soils) requires little technical innovation but better rules and regulation than we currently have, as well as cognisance of the social impact. While there are welcomed increases in the areas of land put aside in the UK and more institutional money flowing, the current certificate system is open to accusations of greenwashing. The chemical side (selectively binding minerals or reagents to CO2 in the atmosphere and storing it underground, underwater or in solid form) feels like it is still at an early stage in terms of innovation and is generally the more expensive of the two. Overall its clear that more progress is needed in both the ecological and chemical sides of capture in order to reduce barriers to investment.

What should we be doing to improve?

In order to meet the IPCC’s targets relating to climate change there are areas in which, as an industry, we need to focus our attention. Below are the three we feel need particular attention.

1. Agricultural sequestration. This ranges from rewilding at one extreme to more sympathetic farming techniques at the other. Unlike CCUS a lot of the technology and efficient practices involved in regenerative agriculture have been around for years, however the social impact of efforts in this sector will need to be carefully managed. Although there is appetite from investors what is lacking are clear frameworks to ensure that the benefits are clearly captured and translate into predictable secure revenue streams for investors.

2. Domestic Insulation. In the UK around 14% of our emissions come from heating our notoriously leaky homes. Improving energy efficiency through insulation has a significant role to play not only in demand reduction but also in facilitating green heating technologies such as air source heat pumps. Currently the economics of doing all but the most basic levels of insulation are hard to justify on a purely commercial basis, so this sector will need improved product innovation, installation efficiency and government support. The private sector can play a significant role in the first two and infrastructure investors are beginning to get involved with transactions like Brookfield’s acquisition of Homeserve.

3. International co-operation. Climate change is the very definition of a global problem. National solutions are important as they are more deliverable and voters in developed countries like their tax revenues spent close to home. However, from an economist’s perspective, the marginal pound should be invested where it makes the most difference, whether conserving Brazilian rainforests or decarbonising Indian heavy industry.